By / Peter Boileau

Washington’s Energy code updates are driven by the Northwest Energy Efficiency Council (NEEC), representing Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. This council is tasked with leading cities, counties, and states in how to reduce energy consumption in the construction of buildings in the future.

Starting with the 2009 energy code, NEEC’s Washington State energy efficiency target is to reduce energy consumption on new residential and commercial buildings from 2006 code levels by 70% by 2031. This will be implemented in eight code updates every three years starting in 2009 and ending in 2030. This ambitious goal means an average of 14% reduction for each code update, compared to the previous code’s requirements, to meet the 70% target.

Energy efficiency goals will be met by multiple methods, such as increasing building envelope insulation, improving thermal performance of glass, and reducing and controlling lighting energy. In addition, the 2015 code now addresses requirements for providing renewable energy and “solar readiness” for new buildings constructed under this code.

For the sheet metal industry, energy required for heating and cooling buildings is a significant component in overall energy use, and therefore our systems are targeted for some of the most radical changes in allowable system types, installation, and operation.

Past energy codes have allowed mechanical system designs to comply with one of two paths—a “prescriptive path” (typically used for simple systems) or a “total performance path,” based on modeling annual energy use of a proposed design and comparing it to energy use modeled using prescriptive path requirements for the same building. This second method allows trade-offs in building envelope components, lighting and power energy, and mechanical system energy. To be code compliant with a total performance path, your design must demonstrate via this computer model that it will use less energy than the prescriptive path model.

With the 2015 energy code, a third option has been added. This option, called “target performance path,” sets maximum annual energy use allowed for different types of buildings but does not dictate how a building must be designed to comply. Instead, this code path utilizes energy metering of the completed building by the code jurisdiction to ensure it uses less energy than the maximum allowable energy target. If the project uses more energy than this target the building owner (and likely the design and construction team) faces significant monetary penalties and continuing remedial work to bring the project into compliance.

The 2015 energy code also contains a new system that deals specifically with existing buildings that are “substantially altered” or upgraded. If your existing building project meets the code definition of a substantial alteration, you will be required to upgrade this existing building, including all envelope, mechanical, and electrical systems, to meet 2015 codes.

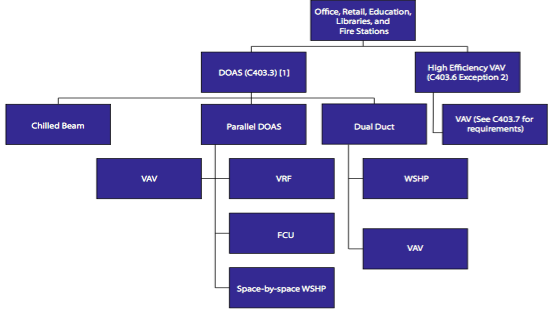

One of the biggest targets for energy reduction in the 2015 code is the use of large, medium to high pressure central fan systems, which have been installed for decades, typically in variable air volume HVAC systems. In the past the use of large fan systems has accounted for up to 25% of the total energy used in a building, and as such is now in the center of the energy reduction target goals. This type of system is still allowed but is now defined in the energy code as a “high efficiency VAV” system. This new definition not only requires higher efficiency cooling and heating source equipment (chillers, boilers, etc.); it also mandates that chilled water systems must be used for cooling if electric heat is desired, and conversely if direct expansion (DX) packaged cooling units are desired, heat must be provided by hydronic boilers. In addition, the 2015 energy code for this type of system requires enhanced controls to measure and at times limit outdoor air cooling and primary supply air temperatures.

The biggest change to this system type (and the biggest impact to our industry) is the limitation on fan energy used in these systems. The limited fan energy requirement includes all fans used in the system (supply, return, relief, and fan-terminal units). This results in duct systems needing to be slightly larger to reduce duct friction to save fan horsepower, but also reducing the pressure class of most primary air duct systems from 4-6” water gauge pressure class to 2-4” pressure class to again save fan horsepower. The net result is typically fewer pounds of ductwork per system when compared to previous code requirements.

The current code now prefers the use of “dedicated outdoor air systems” (DOAS) for providing ventilation and discourages the use of outside air economizers for ventilation and cooling due to the high energy/fan horsepower requirements for delivering large amounts of outside air into (and out of) buildings. DOAS systems provide minimum ventilation required for occupants but do not heat or cool the building. With some exceptions heating and cooling are provided by small “distributed” zone level HVAC equipment such as water-source heat pumps, variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems, fan-coil units, sensible-cooling terminal units, or chilled beam systems. Again, with an eye to reducing fan horsepower these systems use piped systems instead of ducted systems to provide heating and cooling to each area of the building. This results in less ductwork required for a building using these systems, and the ductwork provided is typically smaller in size and lower in pressure class, again impacting our business, as we will be fabricating and installing less ductwork on each project as piping system work increases to meet current and likely future energy codes.

Included above is a simple flow chart that demonstrates the 2015 energy code preference for use of DOAS systems to provide ventilation and the numerous choices for “distributed” HVAC systems when compared to the limited high efficiency VAV system path shown on the right-hand side of the chart. The example below is for 2015 energy code compliance for certain building types as noted below and includes references to the Washington State Energy Code chapters as appropriate. Use these references for further details on how to apply these systems to your project. Also, please note that this article represents my personal understanding of the current code, including several personal opinions on potential impacts, and should be viewed as such.